Response to the proposed Online Safety Act

Reset Australia formerly operated under the name Responsible Technology Australia.

Responsible Technology Australia (RTA) would like to thank the Australian Government for the opportunity to input on the proposed new Online Safety Act. We are excited to see the Australian Government display the leadership needed on this vital issue and look forward to continuing this conversation to ensure appropriate and considered legislation that both protects Australian citizens whilst ensuring that we remain technologically competitive.

Who We Are

RTA is an independent organisation committed to ensuring a just digital environment. We seek to ensure the safety of Australian citizens online whilst advocating for a free business ecosystem that values innovation and competition. In particular, we are concerned with the unregulated environment in which digital platforms currently exist and advocate for a considered approach to address issues of safety and democracy whilst ensuring economic prosperity.

Executive Summary

The focus of this submission is on shifting this regulatory focus and starting a conversation on how we might begin to address the societal harms caused by data exploitation holistically and systematically. Our response to the proposed Online Safety Act, and elaborated further below, is as follows. Responsible Technology Australia:

- Broadly agrees with the proposed approach of the Act concerning content takedown and moderation, which includes the new powers to deal with

- Cyberbullying

- Cyber Abuse of Adults

- Non-consensual Sharing of Intimate Images

- Online Content Scheme

- Blocking Measures for Terrorist and Extreme Violent Materials Online

- Welcomes the positive first steps in establishing the set of Basic Online Safety Expectations however, encourages the Government to consider enforced compliance rather than voluntary

- Recommends convening an Australian working group to contextualise and adapt the UK’s Age Appropriate Design Code as a pathway to better protect children online

- Recommends that the Government consider how an independent regulator could have the remit and be correctly resourced with adequate technical expertise to assess and mitigate these harms, including ensuring how might compliance be enforced both domestically and internationally

1.0 CONTEXT

It is important to recognise that fundamentally, the profit models of digital platforms such as Facebook or YouTube are predicated on the capture and maintenance of user attention. This ‘attention economy’, which directly monetises the amount of time consumers spend on the platforms is optimised through the unfettered and limitless collection of personal data.

As the digital platforms have been building a comprehensive profile of their users that encapsulate their interests, vices, triggers and vulnerabilities, their algorithms have used this information to feed tailored content that is calculated to have the greatest potential of keeping users engaged. This content has been shown to lean toward the extreme and sensational, as it is more likely to be more captivating.

From foreign interference in our democracy, the amplification of fringe and extremist voices that drive division, to threats to the safety of our children, the societal harms caused by this unfettered and unregulated system has permeated our society. In particular, the capacity for granular targeting down to specific communities and even individuals gives rise to a completely unprecedented landscape. Whilst these harms sometimes fall outside of what is considered illegal, their negative effects on an Australian way of life are clearly evident.

Below are a selection of examples of societal harms caused by an unregulated attention economy.

- Foreign Interference: A network of Facebook pages run out of the Balkans profited from the manipulation of Australian public sentiment. Posts were designed to provoke outrage on hot button issues such as Islam, refugees and political correctness, driving clicks to stolen articles in order to earn revenue from Facebook’s ad network. A number of the same accounts Twitter identified as suspected of operating out of the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) targeted Australian politics in response to the downing of flight MH17, attempting to cultivate an audience through memes, hashtag games and Aussie cultural references

- Amplification of Fringe and Extremist Voices: Datasets were collected from six public anti-vaccination Facebook pages across Australia and the US, with it appearing that although anti-vaccination networks on Facebook are large and global in scope, the comment activity sub-networks appear to be ‘small world’. This suggests that social media may have a role in spreading anti-vaccination ideas and making the movement durable on a global scale.

- Safety of Children: A leaked Facebook document prepared by Facebook Australian executives outlines to advertisers their capability to target vulnerable teenagers as young as 14 who feel ‘worthless’, ‘insecure’ and ‘defeated’ by pinpointing the “moments when young people need a confidence boost” through monitoring posts, pictures, interaction and internet activity in real-time.

1.1 EXPANDING ‘ONLINE SAFETY’

Whilst we agree with the Government’s definition of ‘online safety’ as the harms that can affect people through exposure to illegal or inappropriate online content or harmful conduct. We strongly believe that this definition and subsequent policy focus must be expanded to include the ways the digital platforms enable harms not just to individuals but to our communities, democracy and society.

As shown, our current digital architecture has been built to incentivise the propagation of disinformation and division within our communities, resulting in demonstrable harm not just to individuals and communities but Australia as a democratic sovereign state.

It is not just illegal or inappropriate online content or harmful conduct that is causing harm to our society.

We hope through this submission and subsequent collaboration that we might begin to open a conversation on the deeper harms of these systems, how they might be understood and what regulatory methods can be used to tangibly curb their negative influence whilst preserving Australian innovation.

1.2 CONTENT MODERATION

The policies and the new powers proposed in the Online Safety Act around:

- Cyberbullying and content takedown

- Cyber abuse of adults

- Non-consensual sharing of intimate images

- Determination and takedown of seriously harmful material

- Blocking measures for terrorist and extreme violent material online

are vitally important to ensure the safety of all Australians online. RTA is encouraged by these proposed new powers, particularly around reducing the time for takedown and civil penalties for perpetrators of cyber abuse, as they will provide pathways for recourse for victims and more robust mechanisms to ensure illegal content is eliminated online.

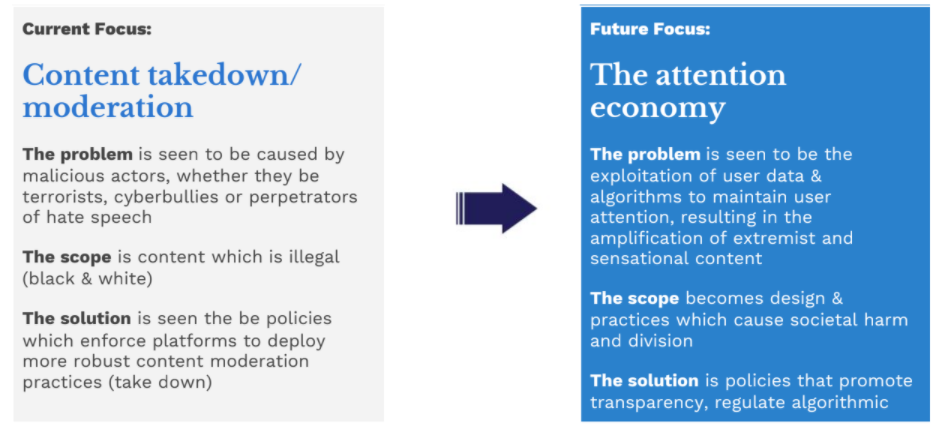

However, these policies (even with their expanded powers) are focused entirely on content moderation and fail to address the deeper structural causes. Whilst we believe it is important for these powers to exist in the new Act, if this is the sole focus, we will forever be left to play catch-up, trying to mitigate the harms caused by content once it has already been distributed and amplified to Australian users. Furthermore, content takedown and moderation policies are not adaptive enough to the types of content - such as unduly polarising, hateful or misinformative content - that is currently legally allowed but nevertheless is the cause of significant harm through inciting hate and violence or intentionally misinforming the public on important issues.

Whilst content moderation policies are an important avenue to mitigate some of the worst of these harms, they are ill-equipped to regulate the profit model of these platforms that exploit user attention and drive vast profit through serving harmful disinformation.

2.0 OBJECTS OF NEW ACT

RTA supports the proposed new high-level objects of the Online Safety Act. In addition to what has been proposed, we believe that there should be a stated commitment to understanding the rapidly evolving nature of this issue.

- Commit to undertaking and supporting the consultation, collaboration and research needed to understand how harms manifest in the Australian digital environment.

3.0 BASIC ONLINE SAFETY EXPECTATIONS

The new Basic Online Safety Expectations (BOSE) are a strong first step to understanding and defining the shared responsibilities required for protecting Australians online. We strongly see the merit in establishing a cohesive set of expectations guided by the proposed process. In particular, the focus around user empowerment and transparency outlined in the Online Safety Charter are especially aligned with our values.

However, we strongly oppose keeping BOSE as a set of expectations ‘enforced’ through voluntary industry reporting. This has been shown around the world to be unsuccessful in achieving the type of protections, 7 transparency and accountabilities that form the core goals of this Act.

Recommendation: Ensure that compliance with BOSE is a legal requirement and enforced.

Recommendation: Ensure that the efficacy of this new regulatory approach by comprehensively calling for all entities that provide services, tools and/or platforms which allow, enable and/or facilitate the generation, interaction or distribution of content should be within the scope of the BOSE

4.0 PROTECTION OF CHILDREN ONLINE

The average Australian teenager spends over 4 hours a day on the internet, with 1.5 being on social media.

The protection of children as they navigate within the digital world is of primary importance. Currently, companies and organisations are keeping Australian children under constant surveillance recording thousands of data points as they grow up. Everything from their location, gender, interests and hobbies, to being able to discern their moods, mental health and relationship status. This information is used to identify particular emotional states and moments where they are particularly vulnerable and used to better target them. Additionally, there have been documented cases, most notably Molly Russel in the United Kingdom , where these algorithmic systems have been shown to directly deliver harmful content that, in Molly’s case tragically resulted in her taking her own life. This illustrates both the egregious harms these platforms can facilitate and the specific vulnerabilities children face in navigating the online world.

In light of this, for the Government’s approach to ‘look to industry to ensure that products marketed to children default to the highest level of privacy and safety at the outset, and enable consumers to set and adjust these controls as they wish’ falls short of the necessary protections required to keep Australian children safe. Whilst it would be preferable for these features to be developed and implemented voluntarily industry-wide, the approach, recommendations and standards must be set by Government - not just to ensure a homogenous environment but to provide the requisite guidance to protect Australian children.

The approach that the United Kingdom’s Government undertook to codify an age-appropriate design for 11 online services where a risk-based approach was used to enshrine 15 standards that seek to protect children within the digital world provides a strong benchmark for Australia to both adopt these learnings and develop a similar code. The code reflects much of the current Australian approach such as defaulting to the most restrictive privacy and safety settings whilst additionally builds on other protections (such as mitigating the effects of nudge techniques and geolocation).

Recommendation: Convene a working group from academia, civil society, business and government to understand and contextualise the UK Age Appropriate Design Code to an Australian ecosystem.

The UK approach exemplifies how the use of children’s data can be made a regulatory priority. Whilst we aren’t necessarily saying that Australia should unthinkingly adopt this code, there is significant value for the Government to reflect the learnings from the UK and initiate a parallel process to adapt and build upon this work for the Australian context.

Recommendation: Require equally strong privacy settings for social media and digital platforms with high rates of usage amongst children.

We welcome the Government’s election commitment of requiring stronger privacy settings for devices and services marketed to children however believe that since many of the digital platforms and social media providers have such a high number of child usage, they should be treated with similar expectations.

5.0 ANCILLARY SERVICE PROVIDER NOTICE SCHEME

We welcome the Government’s recognition that the spread of harmful online content is diverse and quickly evolving. Outside of publication platforms, there are a myriad of aggregator, distribution and broadcasting services that employ the same personal data-driven algorithmic amplification techniques to deliver content. Indeed, it could be argued that it’s through these services in which some of the most egregious effects occur as they have the capacity to exponentially amplify harmful content.

Whilst we support the Government’s proposal for ancillary service provider notice scheme, we believe that for this to achieve the Scheme’s intended outcomes, a couple elements need to be investigated further.

Recommendation: Incorporate ongoing and proactive research and audit of ancillary services to ensure that there is a transparent understanding of how these services propagate online harm.

The mechanics of how these ancillary providers and the role they play in amplifying harmful content is poorly understood and should be thoroughly investigated to build out the necessary evidence base.

Recommendation: Undertake a process to understand how might we additionally empower a regulator in relation to ancillary services and how enforcement might be strengthened.

Firstly, with no sanctions for non-compliance, there is a very limited scope for this scheme to fulfill its objectives. With the current proposal, the regulator would only be empowered to publish reports on service providers who fail to respond. Whilst we recognise that there is a need to balance these powers with the capacity and control these providers actually have over content, we would argue that to be able to truly mitigate online harms, equal attention must be given to the systems used to propagate harmful content.

Powers might include:

- The ability to compel ancillary service providers to respond, provide further information and cooperate

- The ability to ensure transparent reporting of how harmful content is spread through these ancillary service providers

- The ability to proportionately sanction (fine, block, give written notice) to providers who fail to comply

This process should align with our overall recommendations on enforcement below.

6.0 OVERARCHING RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to achieve a regulatory environment which has the flexibility and capacity to ensure a safe online environment for all Australians, we must have an independent regulator that is empowered and resourced to enact the intentions of this Act. As such in addition to commenting on several proposals contained with the Online Safety Act discussion paper, we have provided two overarching recommendations:

RECOMMENDATION | A RESOURCED INDEPENDENT REGULATOR

Recommendation: The Government to undergo a process that explores whether an independent regulator whose role is to evidence and assess the harms of emergent technology should be newly created or incorporated into an existing structure/body through an expansion of powers and remits (eSafety Commission, ACCC, ACMA or otherwise) and subsequently, how. In order to incorporate many of the above recommendations, there should be strong considerations to consolidate these powers into a fully independent regulator. Whilst there might be natural alignment for this to be housed within the eSafety Commission, due to the pervasive ways that unfettered user data collection and algorithmic amplification affect our society, it can be seen that there are significant overlapping responsibilities with the (but not limited to) the ACCC, ACMA, Defence, Australian Intelligence Community, and Attorney-General’s Department. Consolidating responsibility within a centralised and independent body, will ensure that coordination and delivery is timely and efficient.

The possibility of the creation of a new entity, adequately equipped, empowered and resourced (most likely through an industry levy that takes into account factors such as size and scope of impact) to deal with the current and evolving harms should be explored. Whilst there are benefits to this approach such as allowing the independent regulator to better consolidate knowledge and learnings across Government portfolios and functions, be properly equipped to liaise with the civil, academic and private sector and house the necessary technical expertise for governance, research and enforcement. There are also many risks, such as the inefficiencies and potential loss of skill in starting up a new Government body and the lack of clarity in how this new regulator would interact with existing bodies.

Recommendation: The independent regulator must be resourced to conduct ongoing and proactive research and auditing of how the algorithms systems amplify content to users, focusing on the spread of harmful or divisive content. This should include not just hosting services, but ancillary services that aggregate and distribute content.

This regulator must commit to begin to build out the evidence base of the impacts on Australian society that these algorithms are causing. This is vital to both inform future regulation, but to adapt the implementation of the new Online Safety Act.

Topics of immediate concern might include:

- Nature of age appropriate content delivery to children, including violent and sexual material

- Investigate the nature of algorithmic delivery of content which is deemed to be fake news or disinformation

- Audit the extent of algorithmic delivery on the diversity of content to any given user - to investigate filter bubbles

- Audit of the amplification of extremist or sensationalist content by these algorithms

RECOMMENDATION 2 | ENFORCEMENT

Recommendation: Investigate how the powers of an independent regulator might be expanded to incorporate enforcement.

To be effective, a regulator must be able to enforce regulation and go beyond setting transparency reporting expectations. A primary concern we have with many of the current proposals in the Online Safety Act is that many of the enforcement measures rely on voluntary industry compliance with the proposed expectations. We believe that in order for the proposed BOSE to become the normative ‘condition of entry’ to providers operating within Australia, there must be a commitment for the Government to display leadership and ensure these expectations are followed.

Enforcement should incentivise companies to comply whilst providing clear guidelines on how sanctions for non-compliance would be proportionate based on the size of the entity, scale and impact of their potential non-compliance and damage to society.

A wide range of tools could be employed and may include:

- Publishing public notices

- Enforce transparent public reporting

- Issuing provider warnings, reprimands and/or enforcement notices

- Serving civil fines and sanctions

Recommendation: Commit to developing a process that empowers the independent regulator to take action against entities without a legal presence in Australia.

There is an opportunity for the Australian Government to take a world leading role in developing new legal and legislative approaches to adequately deal with the global nature of this issue. It is vital that our independent regulator works with other governments from around the world to coordinate as only an international approach will ultimately be able to mitigate these harms.

What this might look like:

- Setting up multilateral working groups with similar entities internationally

- Adapting a similar concept to the EU’s GDPR of having a ‘nominated representative’ to notionally help enforce compliance

7.0 CONCLUSION

RTA acknowledges the scale of the task ahead to begin to adequately regulate these digital platforms and mitigate the societal harms they inadvertently cause. We look forward to working together to bring about the best outcomes for businesses, consumers and society at large.

Should the Government have any further questions or require further information, we would be happy to engage further.